Man Rescued After Boat Capsizes Off Cape Cod

October 23, 2024

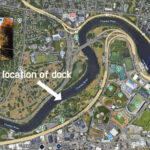

Harvard to Build New Public-Access Dock

October 24, 2024

Welcome to York

Boaters can take a journey into the past on a visit to this protected harbor and scenic river on Maine’s southern coast.

YORK'S STORY

Promoters like to call York “The Gateway to Maine,” and that’s a pretty apt description. But for those arriving by boat, York Harbor also represents a trip from present-day Maine to the coast’s distant past, both literally and figuratively. You start to see it on the approach from seaward, headed for one of the best shelters in the state.

Entering the harbor at a slow pace is the best way begin the “journey into the past” that York offers. At first, you may feel as if you’ve never left Cape Cod and similar environs farther south. That’s because from East Point to the turn at Stage Neck, every stretch of beach is jammed with sunbathers and every inch of shoreline is chock-a-block full of cottages, mansions, hotels, and parked cars.

But as the channel narrows and you leave Stage Neck to starboard, something wonderful happens. In the inner harbor, flashy new shore abodes are replaced by elderly clapboard homes and pleasantly weathered piers. Old dominates and new diminishes. Even better, when you pick up one of the town-managed rental moorings in the swirling waters of the river (don’t try to anchor), the harbormaster or one of his assistants may greet you with a map of York Harbor, and you’ll see that all of “Old York” is well within walking distance.

First settled in the 1620s, York has preserved many buildings from its busy past, including a wharf and warehouse run by Revolutionary War kingpin John Hancock. Farther upriver is the Elizabeth Perkins House Museum, once the home of rough-and-tumble ferrymen and sea captains, but later transformed into a 19th-century summer manse for a well-to-do family. The grounds are spectacular, and open to the public.

In fact, there are nearly a dozen properties scattered about town that have been preserved by various historical groups, and visitors could easily consume several days checking them out. For the saltwater-minded, however, sticking to the river is the best option. Note that traveling by dinghy, skiff, or kayak is the best way to explore the upstream reaches of the York, as it allows easy passage below the various bridges.

Just beyond the Route 103 bridge (15 feet vertical clearance), the river seems to split, with a cheerfully undersized footbridge spanning the mouth of Barrells Millpond to starboard. This miniature suspension bridge is known locally as the “Wiggly Bridge,” which means it’s a bit temperamental underfoot, but otherwise perfectly safe. Best of all, it leads to Steadman Woods, a parcel of land that separates the river from Barrells Cove and which contains some of the most popular walking paths on Maine’s southwest coast.

The bridge and woods are well known to all, but saltwater visitors often look for what is not well known, or even readily seen. Fishermen will be interested to learn that the York River is an ideal spot for pursuing striped bass, especially on the incoming tide. From June until late September, anglers troll the entire upper river for bass, often overlooking the second best fish in town: winter flounder, which can be caught on seaworms fished over mud bottom.

Alternatively, the flood tide can carry you deeper into York’s past, especially if you start early. Beyond Sewall’s Bridge (Rte. 1), there’s a golf course to starboard and just beyond that the remnants of York’s ancient brickyards. As in many early Maine towns, all that thick, heavy clay soil was looked upon as an opportunity to make bricks for export. Cities such as New Haven, Bridgeport, Baltimore, and Philadelphia imported bricks from the likes of York throughout the 18th and early 19th centuries. Today, pieces of those bricks, as well as remnants of the loading piers, can still be seen along the shoreline.

The remains of another early York industry—shipbuilding—can be spied along the southern slopes of the Cider Hill area to starboard, just beyond the Rte. 1 and I-95 bridges. The decaying pilings of piers to which newly launched schooners, brigs, and barques were once tied are still visible at low tide. The old shipbuilding ways are now occupied by subdivisions on Cider Hill, but it’s easy to visualize what once was.

Beyond Scotland Bridge, the last of the river’s overpasses, you may feel as if you’re in the York of 300 years ago. Houses along the shore vanish as you make your way into the upper river’s salt marshes. Looking carefully amid the marsh grass, you may spy weathered fence posts placed by early colonists, who looked upon the marshes as ready-made grazing fields. In late summer, the salt marsh hay was cut and shipped south as another early York export for gardeners along the East Coast.

Riding the tide even farther inland, it’s just you, the egrets, herons, kingfishers, perhaps an osprey or eagle, and, just to remind you of modern times, a strong likelihood of kayakers. The soothing and nearly pristine scenery serves as yet another gateway to Maine and its motto: “The way life should be.”

YORK GALLERY

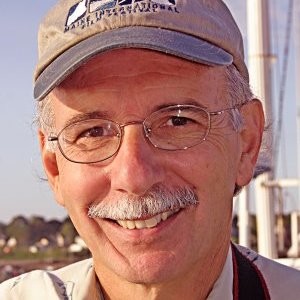

Written by Ken Textor

Ken has ranged the Maine coast by land and sea since the late 1970s. His writing has appeared in WoodenBoat, Cruising World, SAIL, Offshore, Northeast Boating, Points East, Sailing, Yachting, and more. You can find his books on Amazon.

Photographed by Joe Devenney

Joe has many regional and national magazines magazine credits. His images can be found on Getty Images. Joe along with his wife Mary are accomplished potters. Their work may be found at Devenney Pottery on Facebook.